The Day John F. Kennedy Was Laid to Rest: A Nation Stunned and in Mourning

By Verne Strickland (age 26 at the time of this writing)

By Verne Strickland (age 26 at the time of this writing)

We headed for Washington, D.C., on November 24, 1963. It was

a bright but cold Sunday as we rolled out of Raleigh in the waning afternoon.

There were three of us – Will Rogers, executive secretary of the North Carolina

Farm Bureau; Thomas Daniel, vice president, from Wilson, who had joined us in

Raleigh for the trip; and myself. I was director of information for the organization.

Little was said on the six-hour trip up. We mostly stared at

the passing scenery as the radio – giving continuous coverage of the crushing

drame which was unfolding – forced us deeper into our own thoughts over what

had taken place.

Surprisingly, the traffic on U.S. 1 Highway was not heavy.

It thickened some as we approached Washington, but never appeared to be

unusually heavy. We commented on this several times.

The first sight of Washington made my heart strike with a

dull, reverberating thud. The commentators on the radio, it seems, had prepared

us for this. We did not enter the city

that night. But as we neared the Potomac, we could see the Capitol

Building shining cream-colored there amidst a sea of twinkling lights on a deep

field of black. The President’s body lay there in state, and knowing that it

was there seemed to hush our emotions as well as our voices. Washington was in

mourning.

We found a motel at our first stop. This, too, surprised us,

for we were aware that thousands upon thousands had flocked to Washington to

pay their respects to the late President. We all turned in about 1:00 a.m. But

even with the lights out, we continued to leave the television going, and watched

intently from our beds. At about 2:00 a.m., the station concluded its

broadcasting for the day, and we fell into fitful slumber.

As we had ordered, we were aroused by telephone at 4:30 a.m.

Somehow we had no trouble waking and moving about as we prepared ourselves to

leave. The television was again snapped on. We saw an unending procession of

mourners filing through the Capitol Rotunda past the bier which bore the

flag-draped coffin of President Kennedy. Sorrow-inspiring organ music in a

minor key was the only sound emanating from the television. It was as if the

announcer felt nothing could be added.

It had been cold in the room. But outside in the pitch black

of early morning the cold was biting and bitter. As I had no overcoat, I had

bundled myself in two pairs of pants, three undershirts, a sleeveless sweater

and my black woolen blazer. I had questioned my appearance in the fact that my

blazer bore silver buttons. Even this seemed to me gaudy at the time.

There was no heat in the automobile – a long, roomy station

wagon. Thus, the interior was barely warmer than the air outside. There were

stars above as we crossed the Potomac by way of a bridge. Other cars moved with

us and met us. And there was the Capitol in the distance. Agreeing that the

crowd of mourners must have thinned by this time, we headed straight for the

Capitol. It was our intention to file past the bier if there was opportunity.

In the city, things were different. In the dark, people

could be seen in patches on the sidewalks. Cars moved about, but not in number.

We parked a block from the Capitol building and began mounting the long series

of stone steps to the Capitol’s rear entrance.

We began to think that

the television reports must have been in error. Though there must have

been an unusual amount of people out for that time of morning, we commented

that our assumption must have been right – perhaps the line gathered for the

quick trip through the Rotunda had dwindled. Certainly few people would have

the fortitude to stand in line through such a hard-cold night.

Big globes cast a cold light on us as we mounted the steps.

All around us were the hushed voices of black figures whose features were hard

to distinsguish in the pale globes’ glow. I happened that we had approached the

Capitol from the opposite side of the line, as a policeman explained. We should

have known, as more people were descending the steps than ascending.

A few lights, curtains drawn, were lighted. I wondered what

person must be inside, and what he must be doing. I felt small as I

contemplated the sad, awesome business he must be about.

The line. We saw it as we finally rounded the stone corner

to the front of the Capitol, and passed under a lofty archway. It stretched

down the innumerable steps and out of sight in the dark to our right. A

policeman would not let us nearer, perhaps fearing that we might break the

line. He told us that it stretched for 28 blocks, and that some of the people

might not even get inside before the Rotunda was closed at 10:00 a.m. It

happened that he was right.

We decided to leave. People to the the side of the Capitol

shaded their eyes and peeked curiously through locked glass doors of the

tremendous building. We left under a sky now a fading blue-gray. Dawn was

approaching. We found our way to Union Station, where we decided to have

breakfast. Inside there was a great amount of activity. People walked about,

and others sat on the many hard-backed wooden benches and napped.

We had to stand in line to eat. We seated ourselves and

noted diners all about us engrossed in newspapers whose heavy black headlines

told the still stark news of the day. The waitresses, seemingly old and

wrinkled, joked with us and two fellows seated nearby. It did not somehow seem

in bad taste.

Mr. Rogers and Mr. Daniel decided we should go the St.

Matthews’ Cathedral to station ourselves and wait for the procession. I had

suggested going to Arlington Cemetery for the interment which was scheduled for

mid-afternoon. I consented to the Cathedral trip, not realizing that they meant

for us to remain there. The dawn had not fully arrived as we parked in a small

lot, already filling with

mourner-bearing automobiles.

The walk to the Cathedral – some four or five blocks distant from the parking lot – was one I shall never forget. At that early hour, crowds had already begun to deepen on the curb along the procession route. Some men, dressed only in suits, hunched their shoulders against the cold. We passed clusters of figures sleeping figures lying on the sidewalks at the feet of those who stood. One prone figure had a blanket pulled over his head. I saw a fellow walking along carrying an Army sleeping bag. He appeared to be just arriving. Though we were only three among thousands, I seemed to feel that we were about business, and had a purpose in being there. We reached the Cathedral, and decided to go inside before claiming a spot on the sidewalk. The curb had only a single line of people at that time.

The Cathedral, from the outside, was bulky and heavy in

appearance, with none of the grace nor pomposity I had expected. Its

red-bricked exterior seemed small considering the occasion of which it was

destined to be a part. Inside, though, it was lofty. The exterior had been

deceiving. It was almost full, and some sort of service was going on at the

altar. A gloriously-robed priest moved about there and uttered phrases in

Latin. I fought down a whisper of a feeling that I was invading the Cathedral’s

sanctity because I am Protestant. We remained only a moment there at the rear

of the church, and then went back out.

(I wrote no further at this time, but later penned a poem

about the whole experience. It seems to extend the narrative you’ve seen here.)

IN MEMORIAM, JOHN F. KENNEDY

“Waved his hand while time was waning, rode the streets

where Death did wait. Infamy its head was rearing on that day in Texas State.

“Bright the sun shone there in Dallas. Smiling crowds stood

row on row. Black the heart that looked upon it. Black the day life’s blood did

flow.

“By his side was one who knew not what the day would chance

to bring. Smiled she, too, until a bullet caused a funeral dirge to ring.

“Those of us who only knew him, as we watched him from afar,

like as not felt, too, the void which

from that day her joy would mar.

“Weep we now for that young widow. Pray we, too, the scythe

of time may from here heart extract the scars which blemish thoughts of days

sublime.

“Sublime? Oh, no! For days on earth are filled with thorn as

well as rose. And her days here, without her mate, must surely rhymes of tears

compose.

*************

“Walked a street where rolled the caisson that his lifeless

body bore. Stood in crowds, bent now in sorrow, felt the sting of Nevermore.

“Cold the wind blew in that city, where the cortege,

weaving, crept. Stirred, then, thoughts of colder clime, which would his

now-stilled form accept.

“O’er his casket watched the colors that he hailed and

served and sought to keep a-waving that this Nation strong would stay. And this

was wrought.

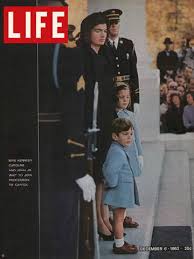

“Black lace shielded by the grave the tears which from those

dark eyes fell. Dust to dust, and ash to ashes. Take him now. He served Thee

well.

“White-gloved hands then rushed to fold this flag for which

he so did care. Impassioned, vowed we to remember that the torch is ours to

bear.

“Hearts were hushed as ‘cross the river floated soldier’s

sad drum roll. We are here to face tomorrow. God have mercy on his soul.”