John Kerry in war and peace: U.S. allies would be right to question his reliability

Special to WorldTribune.comBy Donald Kirk, East-Asia-Intel.com

The U.S.-Korea relationship is about to undergo a major transition, and that’s not just because Lee Myung-Bak is stepping down after five years in which his American advocates professed their love for him even as his popularity sank ever lower at home. The big difference, from the U.S. perspective, is the likely appointment of a new secretary of state, John Kerry, whose view on Korea may well be quite different from that of his predecessor, Hillary Clinton.

There’s no certainty that Kerry, on the basis of his record from the Vietnam War onward, will be in favor of all the military support the United States guarantees South Korea. The record shows Kerry as an anti-war figure from his student days, a Vietnam War hero who turned against the war and an early advocate of U.S. intervention in Iraq who turned against the U.S. role there too.

So who’s to say where Kerry would end up on Korea? As chairman of the U.S. Senate foreign relations committee, he’s called for dialogue between North and South Korea and between the U.S. and North Korea. It’s not a matter of “rewarding bad behavior,” he’s said, but common sense to negotiate.

He might have been a little disillusioned when North Korea in April launched a long-range missile six weeks after signing off with the U.S. on a “moratorium” on nuclear and missile tests and one week after North Korea’s UN representative solemnly informed him of the North’s intent to honor the deal. Still, it’s a safe bet that Kerry will see dialogue as the next essential step for Korea, North and South.

That’s fine, but where would Kerry stand if the dialogue goes nowhere, or if it results in an agreement that’s quickly broken, or if the North stages another incident in the Yellow Sea, a campaign, perhaps to snatch back one of those islands within easy eyesight of North Korean shore gunners?

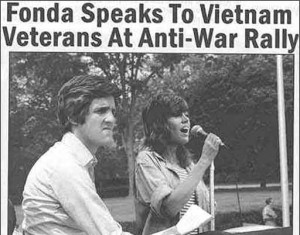

Those are questions for which Kerry’s record provides no sure answers. After serving as a navy officer on a Swift boat on patrol against Viet Cong forces in the vast Mekong River delta of South Vietnam, he returned as an anti-war founder of Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

Kerry was no ordinary protester. He made a show of throwing away his medals, which included a silver star for bravery and three purple hearts for wounds that did not require hospitalization. Kerry’s antics were enough to get President Richard Nixon to ask who this guy was and how he came to have such a strong anti-war viewpoint. Kerry answered that question in testimony before a congressional committee in which he enumerated war crimes, the destruction of villages, the alienation of Vietnamese by the rough tactics of U.S. forces.

Kerry’s position on the U.S. role in Vietnam struck a popular chord in the U.S. as protest rose to the point at which the U.S. withdrew its troops in 1973, two years before the North Vietnamese stormed south on the way to victory.

Many people would commend him for contributing to understanding the horrors of the war.

Many, however, would accuse him of betraying the U.S. forces in which he served, of denigrating the sacrifices of those who also served in Vietnam and of misunderstanding the feelings of millions of South Vietnamese who looked to the U.S. to defend them. In quite a different way, Kerry has gone through reversal on Iraq. Yes, he supported President George W. Bush’s decision in 2003 to wage war against Saddam Hussein, but he completely reversed himself when he ran for president against Bush in 2004 on an anti-war platform.

All of which raises huge doubts as to where Kerry would stand on the U.S. role in conflict anywhere. We can be pretty sure that Kerry, as secretary of state, would declare ritual support of the U.S.-Korean defense treaty, as would anyone in that position. He would enthusiastically call for dialogue with North Korea and would proclaim close ties with the incoming South Korean government.

The question, though, is how he would respond in a crisis. How strongly would he want to face down the North? Would he go for the peace treaty that Pyongyang has long been demanding with Washington? I don’t know of anyone who sees a U.S.-North Korean treaty as anything other than a gambit to separate the U.S. from its South Korean ally and press for withdrawal of U.S. forces, but would Kerry fall for it s a gesture to bring about reconciliation?

Questions about his dedication to America’s allies would extend to Japan and Taiwan. The U.S. has said it would honor its defense relationship with Japan if the current stand-off on the Senkakus were to explode in armed conflict. One has to wonder, though, if he would share this sentiment. Or would he be more anxious to appease Beijing than to defend American allies?

Kerry’s record on foreign policy has been one of dramatic shifts. The history shows he’s loudly opposed U.S. forces at critical moments. Assuming he does become secretary of state, watch out for double-talk, shifting positions and uncertain loyalties.

No comments:

Post a Comment